Published by Rachel (Mathes) Davis, DVM, MS, DACVO October 2016

Publication: Veterinary Information Network (VIN)

Disease Description

Uveitis is a general term referring to inflammation of the vascular tunic of the eye, encompassing the iris, ciliary body and choroid.1 The term uveitis is typically used to reference anterior uveitis or inflammation of the iris (iritis) and ciliary body (cyclitis). The ciliary body component is clinically presumed as cyclitis is typically a histopathologic diagnosis due to the location of the ciliary body in the eye. Thus clinically, uveitis is usually described based on changes to the iris and other visible anterior segment structures in the eye. Although uveitis technically encompasses inflammation of all vascular tunics, more descriptive terms are typically used when referencing posterior segment or complete ocular inflammation.2 Choriodal (+/- retinal) inflammation, termed choroiditis or chorioretinitis, may occur independently of or concurrent with anterior uveitis, depending on the underlying cause. Endophthalmitis refers to inflammation of the iris, ciliary body and choroid with concurrent pathology to surrounding intraocular structures. Panuveitis refers to inflammation of the vascular tunic as well as entire globe and may result in signs of orbital disease depending on the severity of disease.

Etiology

Uveitis is a general term that does not denote any specific underlying etiology.3 The causes of uveitis are numerous and, in part, depend on the cat’s geographic location, travel history, environment, age, sex and breed. Several grouping categories have been proposed to help further classify underlying causes of uveitis. Etiologies may be classified based on endogenous or systemic causes (e.g. infectious, neoplastic) and exogenous or external causes (e.g. toxic, traumatic, radiation).2 Typically, exogenous causes can be readily identified (e.g. penetrating ocular injury, cat fights, etc.). Endogenous causes of uveitis are far more common than exogenous and, as such, can be difficult to elucidate or require further diagnostics.

The most common causes of endogenous feline uveitis include FIP, FIV, FeLV and Toxoplasma gondii.2,4,5 A recent study did not identify an underlying etiology in 40.8% of cases.4 Bartonella spp. has been implicated in feline uveitis, although a direct causal role has not been definitively determined.4,6 Neoplasia may also cause feline uveitis with lymphoma,7 which may ocular as a primary disease or secondary to leukemia, intraocular melanoma,2 intraocular sarcoma,2,8 or metastatic ocular disease being the leading causes. Other causes of feline uveitis, though not as common, have been identified and include leishmaniosis,9 primary immune-mediated neutropenia,10 E. cuniculi,11 Enterococus faecalis,12 Actinomyces spp,13 septic peritonitis,14 and fungal disease.15-17

Diagnosis

Ophthalmic Examination Findings: The ophthalmic findings may vary considerably depending on the duration, severity and nature of the uveitis. Consistent findings of anterior uveitis include rubeosis, iridal swelling, “sluggish” or absent iris movement and flare, the hallmark of uveitis. Miosis is typically also observed, although mydriasis may be present if secondary glaucoma is present.18 Sluggish iris movement may be noted as slow or minimal PLR responses or may also be seen as incomplete pharmacologic mydriasis (dilation) if topical atropine or tropicamide is instilled. Flare, caused by the Tyndall effect,19 is due to increased cell content of the aqueous from leakage of the iridal vessels and is assessed by using the slit beam aperture on a focal light source and viewing the anterior chamber from the side (or holding the light source to the side and viewing the eye centrally). Depending on the severity of the anterior uveitis, hyphema, hypopyon, intraocular fibrin, pre-iridal fibrovascular membranes, cataracts, iridal darkening, corneal edema, keratic preciptates and/or obscured visibility of intraocular structures may be present. Choroiditis or chorioretintis may be seen as intraretinal edema, hyporeflectivity or absence of the tapetal structures, granulomas, retinal detachment, yellow to tan intraretinal or intrachoroidal infiltrates. If panuveitis or endophthalmitis is present, posterior segment pathology may be obscured by anterior changes and may not be fully recognized. Depending on the severity of the uveitis, vision may be decreased or absent.

Non-specific ophthalmic findings may also include blepharospasm, photophobia, conjunctival hyperemia, scleral injection, ciliary flush and enophthalmos with third eyelid elevation.1

Physical Examination Findings: Although some cats with uveitis may be otherwise healthy, the more common causes of uveitis in cats typically cause concurrent systemic illness. A thorough physical examination and clinical history are important when assessing feline patients with uveitis.

Disease Description in this Species

Signalment

Uveitis may affect any age, breed or sex of cat, although male, domestic, middle-aged cats are overrepresented.4

Clinical Signs

Ophthalmic findings: rubeosis, iridal swelling, flare, sluggish iridal movement, miosis (unless secondary glaucoma present), hyphema, hypopyon, keratic precipitates, intraocular fibrin, loss of iridal detail, pre-iridal fibrovascular membranes, cataracts, iridal darkening, corneal edema, intraretinal edema, hyporeflective tapetum, loss of tapetal structures or detail, subretinal granulomas, retinal detachments, choroidal tan to yellow infiltrates, tan to yellow vitreal aggregates or “haze,” blepharospasm, conjunctival hyperemia, scleral injection, ciliary flush, enophthalmos, decreased vision

Clinical signs: highly varied, may be otherwise normal, cutaneous lesions, draining tracts, lameness, weight loss, anorexia, malaise, tachypnea, abdominal pain, abdominal or thoracic masses, hematologic abnormalities, many others

Etiology

- Exogenous – trauma, toxin

- Endogenous – see list

Breed Predilection

- Domestic

Sex Predilection

- Male

Age Predilection

- Middle aged (mean 7.6yr)

Diagnostic Procedures

Ocular ultrasound: Cases of severe anterior segment pathology in which deeper intraocular structures are obscured may be evaluated using ocular ultrasound. This modality may help to further characterize intraocular pathology and assess for intraocular neoplasia, lens rupture or trauma.

Aqueocentesis: Anterior chamber aspiration (aqueocentesis) has not been shown to be a useful diagnostic tool when assessing uveitis in most cases. One study showed no benefit for feline cases20 while another study suggested that it may be helpful when diagnosing lymphoma.21 However, feline lymphoma is typically readily diagnosed using other systemic imaging and sampling modalities. Because aqueocentesis is of questionable value in feline cases of uveitis, requires general anesthesia and carries risks of worsening uveitis, lens trauma, intraocular bleeding or iris trauma, it is not typically recommended for use in cases of feline uveitis.

Ophthalmic examination: Because many changes present with anterior uveitis or chorioretinitis are difficult to fully characterize and often require magnification and advanced training for full evaluation, referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist may be warranted for patients affected with uveitis.

Systemic diagnostics: If exogenous causes and endogenous primary ocular causes are ruled out, systemic diagnostics are recommended in cases of feline uveitis. A baseline CBC and chemistry may be performed to assess general health. In many cases, this diagnostic is normal and further infectious disease testing (e.g. FIP, FIV, FeLV, toxoplasmosis, etc.) and imaging (e.g. thoracic radiographs, abdominal radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, etc.) are warranted. PCR testing for Bartonella spp., Toxoplasma gondii and FHV-1 may help in detection of FHV-1 and T. gondii; however, the usefulness of these tests is still unclear.22 Other diagnostics such as lymph node aspirates and abdominocentesis may be warranted depending on other clinical findings. In some cases, an underlying cause is not identified (idiopathic) or autoimmune disease is diagnosed based on exclusion of other causes.

Images

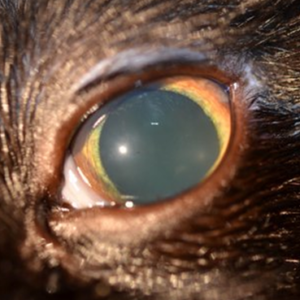

Figure 1. The left eye of a cat affected with uveitis secondary to toxoplasmosis is depicted. There is iridal rubeosis and loss of iris and lens detail, indicating flare and mild corneal edema. Mydriasis is also present, indicating early glaucoma.

Figure 2. The left eye of a cat affected with uveitis secondary to lymphoma is depicted. A slit-beam highlights the moderate flare and multifocal dense keratic precipitates adhered to the endothelium. There is also secondary mild corneal edema.

Treatment/Management/Prognosis

Specific Therapy

Specific therapy depends on identification of the underlying cause of uveitis. Topical anti-inflammatory steroidal (e.g. prednisolone acetate, dexamethasone) and non-steroidal (e.g. diclofenac, flurbiprofen) medications may be used in conjunction 2-4x per day depending on the severity of the uveitis.2,3,23 Topical steroids may precipitate recrudescence of feline herpes virus-1 (FHV-1), which is carried by many cats.24 Client education is warranted regarding signs of FHV-1 and need to discontinue topical steroidal medications if these signs are noted. Oral anti-inflammatory therapy using steroids or NSAIDs may be pursued once the underlying cause of uveitis is identified. Both oral prednisone and meloxicam have been shown to decrease intraocular inflammation in cats.25 Oral steroids may worsen or mask infectious disease if concurrent systemic therapy is not instituted and many NSAIDs are not well tolerated by or advocated for use in cats, thus careful administration of these medications, if used, is recommended.

Supportive Therapy

Topical cycloplegics (e.g. atropine) may be used to help prevent posterior synechia, provide analgesia and decrease ciliary spasm; however, their use should be judicious and patients on these medications should be closely monitored as cycloplegics may potentiate or worsen secondary glaucoma.2 Oral immune modulating therapy (e.g. azathioprine, cyclosporine) may be useful for cases of idiopathic or lymphoplasmacytic uveitis; however, infectious and neoplastic causes of uveitis should be ruled out prior to their use. Subconjunctival steroids are not recommended in cats based on the risk for FHV-1 recrudescence.26

Monitoring and Prognosis

Patients with uveitis are at risk for vision or globe threatening complications, thus close monitoring, identification of underlying cause/s, prompt systemic work up and/or referral to an ophthalmologist are warranted when diagnosing uveitis. The prognosis is dependent on the underlying cause of uveitis. Client education regarding the severity of the disease and need for identification of underlying pathology is also important. Monitoring for secondary glaucoma with frequent intraocular pressure evaluation (every 1-4 weeks depending on the severity and nature of the uveitis) should also be recommended.

Differential Diagnosis

Other ocular conditions causing corneal edema, conjunctival hyperemia or scleral injection

References

- Townsend WM. Canine and feline uveitis. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2008 Mar;38(2):323-46.

- Stiles J and Townsend WM. Feline Ophthalmology. In Gelatt KN (ed): Veterinary Ophthalmology 4th ed. Pg 1117-27. Blackwell Publishing, Ames IA

- van der Woerdt A. Management of intraocular inflammatory disease. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract. 2001 Feb;16(1):58-61.

- Jinks MR, English RV, Gilger BC. Causes of endogenous uveitis in cats presented to referral clinics in North Carolina. Vet Ophthalmol. 2016 Jul;19 Suppl 1:30-7.

- Stiles J. Ocular manifestations of feline viral diseases. Vet J. 2014 Aug;201(2):166-73.

- Stiles J. Bartonellosis in cats: a role in uveitis? Vet Ophthalmol. 2011 Sep;14 Suppl 1:9-14.

- Nerschbach V, Eule JC, Eberle N, et al. Ocular manifestation of lymphoma in newly diagnosed cats. Vet Comp Oncol. 2016 Mar;14(1):58-66.

- Scurrell E, Trott A, Rozmanec M, et al. Ocular histiocytic sarcoma in a cat. Vet Ophthalmol. 2013 Jul;16 Suppl 1:173-6.

- Pennisi MG, Cardoso L, Baneth G, et al. LeishVet update and recommendations on feline leishmaniosis. Parasit Vectors. 2015 Jun 4;8:302.

- Waugh CE, Scott KD, Bryan LK. Primary immune-mediated neutropenia in a cat. Can Vet J. 2014 Nov;55(11):1074-8.

- Künzel F, Peschke R, Tichy A, et al. Comparison of an indirect fluorescent antibody test with Western blot for the detection of serum antibodies against Encephalitozoon cuniculi in cats. Parasitol Res. 2014 Dec;113(12):4457-62.

- Donzel E, Reyes-Gomez E, Chahory S. Endogenous endophthalmitis caused by Enterococcus faecalis in a cat. J Small Anim Pract. 2014 Feb;55(2):112-5.

- Westermeyer HD, Ward DA, Whittemore JC, et al. Actinomyces endogenous endophthalmitis in a cat following multiple dental extractions. Vet Ophthalmol. 2013 Nov;16(6):459-63.

- Pumphrey SA, Pirie CG, Rozanski EA. Uveitis associated with septic peritonitis in a cat. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio). 2011 Jun;21(3):279-84.

- Tofflemire K, Betbeze C. Three cases of feline ocular coccidioidomycosis: presentation, clinical features, diagnosis, and treatment. Vet Ophthalmol. 2010 May;13(3):166-72.

- Pearce J, Giuliano EA, Galle LE, et al. Management of bilateral uveitis in a Toxoplasma gondii-seropositive cat with histopathologic evidence of fungal panuveitis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2007 Jul-Aug;10(4):216-21.

- Gionfriddo JR. Feline systemic fungal infections. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2000 Sep;30(5):1029-50.

- McLellan GJ, Teixeira LB. Feline Glaucoma. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2015 Nov;45(6):1307-33.

- Lam DL, Axtelle J, Rath S, et al. A Rayleigh Scatter-Based Ocular Flare Analysis Meter for Flare Photometry of the Anterior Chamber. Transl Vis Sci Technol. 2015 Dec 11;4(6):7. eCollection 2015.

- Wiggans KT, Vernau W, Lappin MR, et al. Diagnostic utility of aqueocentesis and aqueous humor analysis in dogs and cats with anterior uveitis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2014 May;17(3):212-20.

- Linn-Pearl RN, Powell RM, Newman HA, et al. Validity of aqueocentesis as a component of anterior uveitis investigation in dogs and cats. Vet Ophthalmol. 2015 Jul;18(4):326-34.

- Rankin AJ, Khrone SG, Stiles J. Evaluation of four drugs for inhibition of paracentesis-induced blood-aqueous humor barrier breakdown in cats. Am J Vet Res. 2011 Jun;72(6):826-32.

- Powell CC, McInnis CL, Fontenelle JP, et al. Bartonella species, feline herpesvirus-1, and Toxoplasma gondii PCR assay results from blood and aqueous humor samples from 104 cats with naturally occurring endogenous uveitis. J Feline Med Surg. 2010 Dec;12(12):923-8.

- Gould D1. Feline herpesvirus-1: ocular manifestations, diagnosis and treatment options. J Feline Med Surg. 2011 May;13(5):333-46.

- Rankin AJ, Sebbag L, Bello NM, et al. Effects of oral administration of anti-inflammatory medications on inhibition of paracentesis-induced blood-aqueous barrier breakdown in clinically normal cats. Am J Vet Res. 2013 Feb;74(2):262-7.

- Nasisse MP, Guy JS, Davidson MG, et al. Experimental ocular herpesvirus infection in the cat. Sites of virus replication, clinical features and effects of corticosteroid administration. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1989 Aug;30(8):1758-68.