Published by Rachel (Mathes) Davis DVM, MS, DACVO August 2016

Publication: Veterinary Information Network (VIN)

Disease Description

Uveal melanomas, albeit relatively uncommon in general, are the most common primary intraocular tumor in dogs and occur in dogs more than any other species.1,2 Uveal melanomas are considered benign in this species, although metastasis has rarely been reported.3-5 The term “melanocytoma” is typically reserved for benign melanocytic tumors and may be a more appropriate term when referring to canine uveal melanomas, although there is significant cross-over between terms in the literature when referring to these tumors in dogs.2 Uveal melanomas most commonly arise from the iris or ciliary body with primary choroidal melanomas being rare in dogs.6-10 Differentiating a primary iris or ciliary body tumor may be difficult when large intraocular masses are present and has little clinical relevance in how the tumors behave. However, the location of the tumor may be clinically relevant in determining treatment options.

Etiology

Uveal melanomas arise as primary, typically benign, intraocular tumors in dogs.11 Even though uveal melanomas do not tend to metastasize, they may be locally aggressive and will expand to involve other intraocular structures over time. Although a case report exists describing metastasis of a nail bed melanoma to the right eye, pigmented intraocular tumors are almost always primary uveal tumors in dogs.12

Diagnosis

Ophthalmic Examination Findings:

Early tumors typically appear as raised, well-demarcated, focal, brown or black intrairidal masses within the iris body or at the iris base, especially if emerging anteriorly from a primary ciliary body melanoma. Brown or black intrairidal masses should be differentiated from iris cysts based on transillumination or ocular ultrasound. Uveal melanoma may be missed in the early stages of disease because the iris in most dogs is normally deeply pigmented and the tumor may be somewhat obscured visually. Thus, patients may not present to the clinician until the tumor has become quite large. In this later stage, tumors may appear as large, pigmented intraocular tumors and may cause dyscoria, secondary glaucoma, anterior uveitis, hyphema, buphthalmos, lens subluxation, ocular pain, retinal detachments or blindness.13,14 Depending on the stage of glaucoma and whether there is uveitis or hyphema, it may not be clinically apparent on presentation that an intraocular tumor is present based on ophthalmic examination alone.

Clinical Examination Findings:

Because canine uveal melanomas are typically benign, full systemic staging is not necessary when suspecting or diagnosing these tumors. However, full clinical examination with particular attention paid to the foot pads, gingiva and skin is warranted. Additionally, a client discussion regarding the possibility of metastasis, albeit rare, should be considered.

Disease Description in this Species

Signalment

Uveal melanomas typically occur in middle-aged to older dogs, but they may occur at any age.11 Uveal melanomas may occur in many breeds, although German Shepherds and Retrievers may be at higher risk.15

Clinical Signs

Early anterior uveal melanomas are typically well-demarcated, raised, roughly circular, brown or black masses seen on the iridal surface in dogs, although they may appear as brown or black flat masses. Unlike iridal nevi or “freckles,” they demonstrate growth over time, although growth may be very slow. Because it may be difficult to distinguish between an iridal nevi and early, small melanoma based on size alone, serial examination, ideally with photographic documentation, of the area is necessary to determine if the pigment is growing.

Later, tumors may appear as large, pigmented intraocular tumors with variable intraocular involvement. Large, invasive uveal melanomas may cause dyscoria, secondary glaucoma, anterior uveitis, hyphema, buphthalmos, lens subluxation, ocular pain, retinal detachments or blindness.14 Depending on the stage of glaucoma and whether uveitis or hyphema is present, it may not be clinically apparent on presentation that an intraocular tumor is present based on ophthalmic examination alone.

Etiology

- Spontaneous

- Neoplastic

Breed Predispositions

- Labrador Retriever

- Golden Retriever

- German Shepherd

- Any breed

Sex Predilection

- None

Age Predilection

Mean age 9yrs, reported in dogs 2mo to 17yr of age11

Diagnostic Procedures

Small brown or black masses noted within the iridal body may be monitored (and ideally photographed) over time to assess for growth. Any larger, solid, pigmented intraocular mass distorting the iris, anteriorly displacing the iris or displacing other intraocular structures may be presumed to be a uveal melanoma, although histopathology is required for definitively diagnosis. Uveal melanomas may emerge through the sclera to affect the perilimbal region, thus making it difficult to distinguish between a primary limbal melanoma and a primary uveal melanoma. Ocular ultrasound and gonioscopy will help determine the extent of the mass and involvement with intraocular structures. These diagnostics will also help distinguish a primary limbal melanoma vs. uveal melanoma.

Images

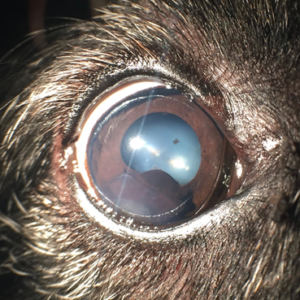

Figure 1. A large, lobulated, pigmented, ventral, intrairidal mass is depicted in a 11yr old MN Scottish Terrier. This tumor had been present for several years with slow growth noted. The patient is comfortable and visual.

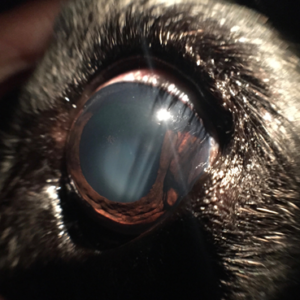

Figure 2a and 2b

A peripheral, pigmented, raised, irregular, smooth, intrairidal mass is depicted in a 13yr old FS mix breed. This mass is causing scleral expansion and a focal staphyloma (scleral bulging) temporally. The patient is visual and comfortable.

Figure 2a and 2b

A peripheral, pigmented, raised, irregular, smooth, intrairidal mass is depicted in a 13yr old FS mix breed. This mass is causing scleral expansion and a focal staphyloma (scleral bulging) temporally. The patient is visual and comfortable.

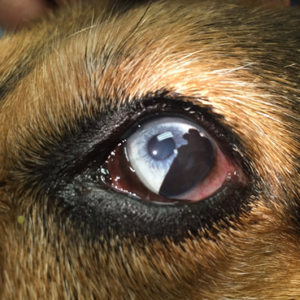

Figure 3

A large, flat, pigmented, irregular, intrairidal mass is depicted in a 6yr old MN mix breed. Transcorneal diode laser therapy was recommended to treat this tumor.

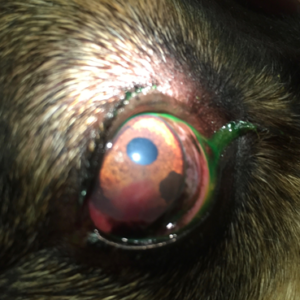

Figure 4

A small, ventral, flat, pigmented, intrairidal area is depicted in a 9yr old FS German Shepherd noted as an incidental finding. Recommendations to monitor this area photographically were made with diode laser treatment if growth was noted over time. A concurrent (unfocused) pannus lesion is also present.

Treatment/Management Prognosis

Specific Therapy

Although uveal melanomas are usually benign, they may be locally aggressive and cause significant intraocular pathology, leading to glaucoma, uveitis and vision loss. Early iris melanomas may be amenable to surgical resection via partial iridectomy, either with traditional methods or utilizing a transcorneal or endoscopic diode laser. Non-invasive transcorneal diode laser treatment of uveal melanomas has a high success rate and is an attractive treatment for uveal melanomas isolated to the iris.16

Lobulated or large melanomas that involve the ciliary body, peripheral choroid or sclera may be monitored over time if there is no other overt ophthalmic disease. Client education regarding recognition of clinical signs caused by secondary painful conditions should be considered a priority, in these cases. In addition, intraocular pressure should be monitored every 4-6 months for slow-growing uveal melanomas. Once glaucoma, uveitis, vision loss or patient discomfort is present, enucleation should be recommended. The globe should also be submitted for ocular histopathology to further characterize the mass.

Supportive Therapy

Any patient presenting with a uveal pigmented mass should have a thorough physical examination with particular attention paid to the footpads, skin and gingiva.2 Topical anti-inflammatory therapy with steroids (e.g. prednisolone acetate, dexamethasone) or non-steroidals (e.g. flurbiprofen, diclofenac) may be instituted for low-grade uveitis caused by uveal melanoma, although these eyes should be closely monitored for glaucoma (i.e. intraocular pressure evaluated initially in 3-4 weeks, then q2-3mo therafter). Antitensive topical therapy for secondary glaucoma is typically ineffective for cases of uveal melanoma and enucleation should be recommended to alleviate discomfort.

Monitoring and Prognosis

Small (<3mm) raised or flat brown or black intrairidal masses noted in a dog iris should be photographically monitored over time (usually q4-6mo), either at rechecks in the clinic or at home with the owner. For larger, raised intrairidal masses or if growth of small masses is noted over time, transcorneal diode laser therapy or partial iridectomy (see specific therapy) may be pursued. If the mass is filling the anterior chamber, causing blindness or causing glaucoma, enucleation should be pursued with histopathology.

Although the metastatic rate is low for canine uveal melanomas,14,17-19 criteria for malignancy of uveal melanomas varies widely among authors with no consensus on identification of malignant versus benign tumors histologically.11,15,17,20 COX-2 expression was similar in globes with and without neoplasia. Additionally, differentiation between malignant and benign masses was not possible using this marker.21 Four of 14 genes that differentiate human metastatic uveal melanoma from non-metastatic disease were elevated in a preliminary canine study, indicating possible future utilization of gene expression as a marker for canine uveal metastasis.22 Clinically, these tumors do not tend to be metastatic; however, a client discussion regarding the possibility of metastasis, albeit rare, should be considered.

Differential Diagnosis

- Intraocular neoplasia (other than melanoma)

- Iris cysts

- Granulomas (parasitic or other)

- Staphylomas

- Ocular melanosis

References

- Ditters RW, Dubielzig RR, Aguirre GD, et al. Primary ocular melanoma in dogs. Vet Pathol. 1983;20:379-395.

- Hendrix DVH. Diseases and Surgery of the Canine Anterior Uvea. In Gelatt KN (ed): Veterinary Ophthalmology 4th ed. Pg 841-3. Blackwell Publishing, Ames IA

- Delgado E, Silva JX, Pissarra H, et al. Late prostatic metastasis of a uveal melanoma in a miniature Schauzer dog. Clin Case Rep. 2016;28:647-52.

- Yi NY, Park SA, Park SW, et al. Malignant ocular melanoma in a dog. J Vet Sci. 2006;7:89-90.

- Rovesti GL, Guandalini A, Peiffer R. Suspected latent vertebral metastasis of uveal melanoma in a dog: a case report. Vet Ophthalmol. 2001;4:75-7.

- Dubielzig RR, Aguirre GD, Gross SL, Diters RW. Choroidal melanomas in dogs. Vet Pathol. 1985;22:582-5.

- Schoster JV, Dubielzig RR, Sullivan L. Choroidal melanoma in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1993; 203: 89-91.

- Hyman JA, Koch SA, Wilcock BP. Canine choroidal melanoma with metastasis. Vet Ophthalmol. 2002;5:113-7.

- Miwa Y, Matsunaga S, Kato K, et al. Choroidal melanoma in a dog. J Vet Med Sci. 2005;67:821-3.

- Steinmetz A, Ellenberger K, Marz I, et al. Oculocardiac reflex in a dog caused by choroidal melanoma with orbital extension. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2012;48:66-70.

- Wilcock BP, Peiffer RL. Morphology and behavior of primary ocular melanomas in 91 dogs. Vet Pathol 1986;23:418-424.

- Esson D, Fahrer CS, Zarfoss MK, et al. Suspected uveal metastasis of a nail bed melanoma in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol. 2007;10:262-6.

- 13. Dubielzig RR. Ocular neoplasia in small animals. Vet Clin N Am Sm Anim Pract. 1990;20:837-48.

- Giuliano EA, Chappell R, Fischer B, et al. A matched observational study of canine survival with primary intraocular melanocytic neoplasia. Vet Ophthalmol. 1999;2:185-190.

- Ryan AM, Diters RW. Clinical and pathological features of canine ocular melanomas. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1984;184:60-7.

- Cook CS, Wilkie DA. Treatment of presumed iris melanomas in dogs by diode laser photocoagulation: 23 cases. Vet Ophthalmol. 1999;2:217-25.

- Wang AL, Kern T. Melanocytic ophthalmic neoplasms of the domestic veterinary species: a review. Top Companion Anim Med. 2015;30:148-57.

- Rovesti GL, Guandalini A, Peiffer R. Suspected latent vertebral metastasis of uveal melanoma in a dog: a case report. Vet Ophthalmol. 2001;4:75-7.

- Minami T, Patnaik AK. Malignant anterior uveal melanoma with diffuse metastasis in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1992;15:1894-6.

- Friedman DS, Miller L, Dubielzig RR. Malignant canine anterior uveal melanoma. Vet Pathol. 1989;26:523-525.

- Paglia D, Dubielzig RR, Kado-Fong HK, et al. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 in canine uveal melanocytic neoplasms. Am J Vet Res. 2009;70:1284-90.

- Malho P, Dunn K, Donaldson D, et al. Investigation of prognostic indicators for human uveal melanoma as biomarkers of canine uveal melanoma metastasis. J Small Anim Pract. 2013;11:584-93.