Penetrating Ocular Trauma – Feline

Published by Dr. Emily A. Latham, DVM

Last updated on 7/15/2024.

Contributors:

Revised by Emily A. Latham MVB and Rachel L. Davis DVM, MS, DACVO

Revised by Pilar Camacho-Luna LV, 11/1/2019

Original author was Ralph E. Hamor DVM, MS, DACVO, 3/16/2012

Synonyms:

Traumatic corneal penetration

Traumatic globe rupture

Traumatic scleral penetration

Disease Description:

Definition

Penetrating ocular trauma refers to any full-thickness injury of the globe from a traumatic event. Sometimes the injury occurs through the cornea and is visible to the observer. Sometimes trauma occurs through the sclera, and direct observation of the injury is obscured by conjunctiva, eyelids, and other orbital tissues. The bony orbit of dogs and cats provides excellent protection of the globe from blunt trauma. The globe is more commonly affected by penetrating trauma. When blunt trauma causes scleral disruption/rupture, the injury is treated like penetrating trauma.1

Etiology

The most common cause of penetrating trauma in cats is from claw scratches or bite wound (Figures 1A, 2).2,3 Introducing a new cat to the home environment can lead to fighting in multi-cat households. Outdoor cats may be more likely to experience cat claw wounds from fighting with other cats. Because outdoor cats tend to roam free, they may return home with injuries of unknown origin.

Various projectiles can penetrate the globe. Animals that roam free are most likely to be exposed to lead or steel buckshot. This type of gunshot wound can affect the whole head and other parts of the body. Migrating foreign bodies that enter the mouth or head may also eventually penetrate the eye. Examples include porcupine quills, sticks, plant awns, sewing needles (Figures 3A, 3B), etc. Aspiration of the orbit or infiltration of injectable anesthetics into the retrobulbar space can potentially result in iatrogenic penetration of the globe, especially with poor technique.

Dental cleaning procedures, especially those involving tooth extractions from the maxillary arcade, can also result in accidental penetration of the globe.4,5 Although uncommon, globe penetration associated with dental procedures is reported more often in cats than dogs.5,16 Due to the close relationship of the orbital floor and tooth roots of cats, extractions of maxillary premolar and molar teeth can lead to iatrogenic scleral perforation and/or lens capsule rupture.19 Severe anterior uveitis may not develop until days, weeks, or months after the procedure from septic implantation syndrome.17 These penetrating injuries are often identified only upon histopathology, after the eye fails to respond to medical treatment and is enucleated.19 Globe penetration was also reported in one cat following a maxillary nerve block.15 The authors of a retrospective study of 13 cats advised against the use of transoral maxillary nerve blocks because of the ocular penetrating injuries that occurred.20

Pathophysiology

Following trauma, alterations within the eye vary depending upon the location and type of injury. All injuries result in secondary uveitis. Aqueous flare, miosis, dyscoria, and swelling/inflammation of the iris may occur. Hyphema and posterior segment hemorrhage can occur. Although minor lacerations of the lens capsule can heal with fibrosis, disruption of the lens can result in cataract formation and phacoclastic uveitis.

Injuries to the cornea may be associated with fibrin deposition at the site of penetration, iris prolapse, and stromal edema. Severe lacerations or penetrating injuries to the cornea and sclera may cause loss of aqueous humor and collapse of the globe. Severe, extensive, or posterior segment injuries may lead to blindness. Retinal detachment is also possible. Involvement of the orbit may result in orbital cellulitis.

Secondary infection (e.g. endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, septic implantation of lens) may develop with exposure to natural materials that decompose over time, such as wood, vegetation, porcupine quills, etc.17 In addition to these items, materials that oxidize (e.g. iron, steel) cause severe intraocular inflammation. Inert projectiles (e.g. gold, silver, stone, carbon, glass, rubber) are less irritating than mercury, lead, aluminum, zinc, and nickel. Materials composed of copper, bronze, and brass may result in localized abscessation.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings/History: Generally, the owner is aware that some sort of acute trauma has occurred. However, it is important to ask questions regarding the animal’s environment, temperament, presence of other pets in the household, the pet’s job, whether it is confined, and its most recent activities. New introduction to other animals, especially cats, may be reported.

If head and/or systemic trauma is obvious, perform oral and physical examinations to determine the extent of injuries elsewhere. Depending on the origin of the wound, periocular hemorrhage and bruising, wounds to the eyelids, head, and face, as well as facial fractures may be detected. More serious systemic injuries (e.g. thoracic, abdominal, subcutaneous) can occur with trauma from projectiles.

Ophthalmic Examination Findings: Examination of the eye is facilitated by application of topical proparacaine. In some animals, sedation or general anesthesia may also be required. Careful manipulation of the eyelids is important to avoid further damage to the globe. All ocular surfaces are examined with magnification. Schirmer tear test and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement are not done in acute cases with an obvious defect of the cornea because of the risk of causing further damage. IOP is only measured if the trauma is thought to be chronic (old). Air bubbles within the anterior chamber are indicative of globe perforation.19

Be sure to assess cranial nerve reflexes, including palpebral reflex, corneal sensitivity, pupillary light reflexes, dazzle and menace responses. Results help determine prognosis for vision and retention of the globe.19

If the equatorial or posterior sclera is penetrated, few overt clinical abnormalities may be noted in the anterior segment. However, subconjunctival hemorrhage is typically present. In these cases, complete examination of the lens, vitreous, and fundus is very important. Dilation of the pupil facilitates a more complete examination. Thorough examination of the opposite eye is also indicated.

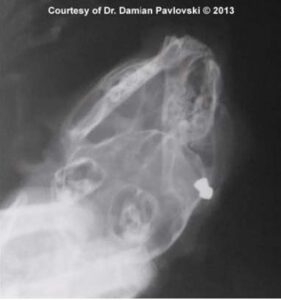

Radiography: Plain radiographs of the skull identify metallic (Figure 4) or bony foreign material and accompanying bony fractures. The location of the eye can be marked with a metallic ring (Flieringa fixation ring) placed on the limbus. This helps identify foreign objects that lie close to or within the globe. Neck, chest, and abdominal x-rays may also be warranted to rule out additional trauma, or the presence of more foreign bodies.

Ultrasonography: An important step following penetrating injury is to determine what ocular structures have been affected. Clinical examination alone may be insufficient for making this determination, especially if opacification of ocular media (e.g. aqueous flare, hyphema, vitreal hemorrhage) prohibits examination of the interior of the globe, or if the rupture is equatorial or posterior. If globe integrity is adequate, ocular ultrasonography may help determine the presence of lens capsule rupture, a foreign body, vitreal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment.17 Ultrasonography is also useful in cases of suspected scleral rupture. However, following penetrating trauma the pressure applied by the probe on the eye can worsen damage to the globe.

Ultrasonography can be done awake, or under general anesthesia when the patient is intractable, painful, or the globe is unstable. Even with ocular ultrasonography, it may not be possible to visualize small tears in the lens capsule, and inflammatory debris or hemorrhage may mask a retinal detachment. Evaluation by a veterinary ophthalmologist may be considered in such instances.

Advanced Imaging: Computed tomography (CT) may be indicated if penetrating injury has been caused by projectiles that may still be present within the eye or have penetrated the skull. Foreign bodies may be easier to identify with CT than plain radiographs depending on the material. CT systems can create 3D reconstructions that are especially useful in evaluation of head trauma and suspected fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging is avoided if penetrating material is potentially composed of ferrous metals.

Other Tests: Bacterial cultures may be positive or negative depending upon the duration and origin of the injury. Cultures are most likely to be positive with endophthalmitis from cat scratch injuries or penetrating material than can necrose (e.g. plant material). High-speed projectiles generate enough heat upon entering tissues that they are unlikely to result in bacterial infections unless the entry wound remains open. Cytology of aqueous humor and other secretions may rarely show bacteria.

Disease Description in This Species:

Signalment

Penetrating injuries in cats are most often associated with cat scratches. Perhaps because of their faster reflexes and immediate tendency to turn and flee, the incidence of penetrating wounds from projectiles and bite wounds is less common than in dogs. Brachycephalic breeds are predisposed to ocular trauma due to their large palpebral

Clinical Findings:

AFEBRILE

Anisocoria, pupils unequal

Anorexia, hyporexia

Bite, puncture wound

Blepharitis

Blepharospasm, eye pain

BLINDNESS OR OTHER VISUAL DEFICIT

Blindness partial, visual deficit

Conjunctival congestion, hyperemia

Conjunctival hemorrhage

CONJUNCTIVITIS

Corneal laceration

Corneal opacity

Corneal scarring

Corneal ulcer, keratitis

Corneal vascularization

Dyscoria

Edema conjunctiva, chemosis

Edema corneal

EDEMA or SWELLING

Edema or swelling cutaneous

Edema or swelling eyelid

Edema or swelling face, head

Edema or swelling orbital, periorbital

Edema or swelling periocular

Endophthalmitis

Enophthalmos

Epiphora, lacrimation increased

Episcleral injection/congestion

Eye small

Eyelid erythema

Facial malformation

HEMORRHAGE

Iris prolapse

Keratoconjunctivitis

Lens luxation, subluxation

MASS

Mass, corneal

Mass, scleral

Menace response absent or decreased

Miosis

MYDRIASIS

OCULAR DISCHARGE

Ocular discharge hemorrhagic

Ocular discharge purulent

Ocular discharge serous

PAIN

PHOTOPHOBIA

Pupillary light reflex absent

Pupillary light reflex decreased

Scleral hemorrhage

Scleral laceration

Synechia, anterior

Third eyelid, nictitating membrane prolapsed

ULCERS

UVEITIS

Uveitis, anterior

Metallic foreign material visualized

Foreign body visualized

Hyperechoic lens

Possible foreign material in eye

Vitreal cavity hemorrhage

Vitreal debris

Cataract, lens opacity

Corneal penetration

Hyphema, blood anterior chamber eye

Intraocular pressure normal or decreased on tonometry if uveitis present

Iridocyclitis, iris/ciliary body inflamed

Iris-to cornea or iris to lens adhesion

RETINAL CHANGES

Retinal detachment

Retinal hemorrhages

Scleral penetration

Third eyelid, nictitating membrane protruded

Vitreous cloudy

Images:

3-yr-old DSH cat with full thickness corneal laceration sealed with a fibrin plug. Note wounds on ventral eyelid margin.

3-yr-old DSH cat with full thickness corneal laceration sealed with a fibrin plug. Note wounds on ventral eyelid margin.

3-yr-old DSH cat. Mild fibrosis persists at penetration site. The eye is quiet and visual.

2-yr-old DSH cat. Iris was prolapsed and lens was ruptured. Full-thickness eyelid laceration is also visible at the lateral canthus.

Oral foreign body penetrating globe in a cat

Penetrating ocular foreign body in a cat

Radiograph of a bullet wound to head and eye in a cat

Treatment / Management:

INITIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Initially, other injuries must be assessed and stabilized. Hemorrhage around the eye should be controlled. After the patient is stabilized, and diagnostic examination and tests are complete, then specific therapy may be instituted. General anesthesia may need to be delayed in the presence of significant head injuries.

SPECIFIC THERAPY

Corneal Wounds

If the rest of the globe is intact (i.e. wound penetrated only the cornea), then a decision must be made as to whether the corneal wound requires repair. Smaller corneal lacerations (i.e. <3 mm) may not require surgery if foreign bodies are not present; the wound is sealed; the anterior chamber is well formed; no leakage of aqueous is occurring; and no iridal/uveal tissue is prolapsed. If unsure how to proceed, then referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended. Superficial corneal foreign bodies may be removed under topical anesthesia if the patient is cooperative. Deeper corneal foreign bodies require removal under sedation or general anesthesia and magnification (e.g. operating microscope).

If the corneal wound is not intact (Figure 1A); a large flap was created; the iris is prolapsed (Figure 2); and/or a foreign body is still present, then surgery to remove the foreign body, and/or repair the cornea is required. The cornea is typically repaired (using an operating microscope) with 8-0 or 9-0 absorbable suture. A conjunctival graft may be placed over the incision after suturing to provide extra support (Figures 1B, 1C). Depending on the location of the wound, conjunctival grafting may reduce vision. Other surgical techniques that may be considered include amniotic membrane and corneal grafts.9,10 These procedures require specialized equipment and expertise and thus referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended.

Scleral Wounds

Usually repair of a scleral rupture is not possible because of the location of the wound, e.g. equatorial or posterior. Because blindness and phthisis bulbi are common sequela, enucleation is often the only treatment option for extensive scleral lacerations.1 For small tears, medical therapy can be attempted, and may provide adequate cosmesis. However, long-term outcome of medical therapy has not been evaluated and the risk of long-term complications (e.g. chronic pain, panophthalmitis, phthisis bulbi, secondary entropion) must be considered.

Eyelid Wounds

Accompanying eyelid lacerations may also require surgery, especially is they involve the lid margin. See the Feline VINcyclopedia chapter on Adnexal Trauma for more information.

Lens Capsule Wounds

If the lens capsule is lacerated, treatment recommendations vary. For many years, lensectomy was advised for capsular tears >1.5 mm, or when substantial herniation of lens cortex material occurred into the anterior chamber.7 Lens proteins are antigens, and exposure of the anterior chamber to large amounts of lens proteins may result in severe granulomatous inflammation (i.e. phacoclastic uveitis) that is unresponsive to medical therapy and can result in blindness. However, small tears may heal by fibrosis, and a retrospective study demonstrated that even large lens capsule lacerations may respond well to medical therapy alone.3 In this study prognosis was better for eyes that were referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist within 72 hours and were followed carefully for the first 2-4 weeks.3 In one study, excellent outcomes were achieved with phacoemulsification and corneal repair for traumatic lacerations involving the cornea and lens.21 Another study reported that >50% of eyes with traumatic corneal laceration with lens capsule rupture lost vision regardless of the therapy.6

An additional factor must be considered in cats with lens capsule rupture because development of intraocular sarcomas has been associated with penetrating trauma to the lens in this species.7,8,11,19 Sarcomas can also occur following chronic uveitis and lens surgery, and in phthisical eyes.12 Enucleation should be considered in feline eyes with lens trauma.

Severe Injuries

Aggressive medical therapy can be tried in less severe cases prior to considering enucleation. However, enucleation is indicated in the following instances:

1) Large wounds that affect both cornea and sclera, with herniation or loss of intraocular contents

2) Expulsive injuries, with loss of the lens and/or collapse of the eye

3) Exposed or through-and-through foreign body

4) Injuries accompanied by orbital fractures that displace the globe

5) Corrective surgery delayed because of systemic injuries

6) Attempts at surgical repair and control of uveitis fail

7) Development of infection, chronic endophthalmitis despite appropriate therapy17

8) Lens trauma that predisposes to future intraocular sarcoma

SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

Supportive medical therapy involves both topical and systemic medications. Topical bactericidal antibiotic solution (e.g. fluoroquinolone, gentamicin, tobramycin) is administered q 4-8 hrs. Ointments are contraindicated because the oil-based carrier is irritating to intraocular structures. Ophthalmic triple antibiotics are avoided because of the possible risk of anaphylactic reactions in cats.13,14 A topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) agent may be administered if hyphema is not present. Topical atropine is given to dilate the pupil and help control pain. Topical anti-fungal agents are often indicated in some cases of vegetative foreign bodies.

Broad-spectrum systemic antibiotics are indicated in many cases. Systemic NSAIDs may be considered once active hemorrhaging is controlled. Systemic pain medication is typically indicated. An Elizabethan collar is applied until the wound heals. Sedation may be needed to keep an anxious or overactive animal quiet for a few days.

Once the corneal wound has healed, topical steroids (e.g. dexamethasone, prednisolone acetate) may be substituted for topical NSAIDs, especially if severe, secondary uveitis is present. If intraocular inflammation is considered to be sterile and uncontaminated, oral steroids may also replace oral NSAIDs after an appropriate wash-out period.

MONITORING

Frequent monitoring is crucial for achieving a long-term, successful outcome. Medical therapy is often required for several weeks to months. Development of delayed complications is common, so recheck examinations are often continued for months. Treatment modifications are made depending upon the findings at each examination. Septic lens implantation syndrome can occur following traumatic injuries to the lens and lead to chronic uveitis.17

Because sarcoma formation can occur years after the initial trauma, affected eyes must be monitored long term for signs of tumor formation (e.g. white to pink intraocular mass(es), progressive enlargement of a previously phthisical globe), chronic uveitis, secondary glaucoma, and intraocular hemorrhage.7,8 For more information see the Feline VINcylopedia chapter on Intraocular Neoplasia.

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis depends on severity of the injury; presence of complicating systemic injuries; time between injury and institution of therapy; appropriateness of therapy; and type and final location of foreign material involved in the penetration. Potential complications include uveitis, hyphema, cornea scarring, cataract formation, permanent anterior synechiae and dyscoria, secondary glaucoma, endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, vitreal opacities, visual deficits or blindness, phthisis bulbi, and sarcoma formation. Lack of dazzle reflex and loss of consensual pupillary light response at the initial examination are poor prognostic indicators for vision.

In many cases, prompt attention and treatment can save vision. Penetration of the lens capsule complicates and worsens the prognosis.3,6 Penetration of the posterior aspect of the globe is also associated with a worse prognosis. If the orbit has suffered significant damage, it is more likely the globe cannot be salvaged.

Preventive Measures:

Take precautions when introducing a new cat to a household with other cats. Trim the cats’ nails short, or apply soft paws prior to bringing the new cat home. Make the introduction a gradual one, under close supervision. Until the cats are well accustomed to each other, consider separating them when they are left home alone. Do not allow cats to roam free.

Special Considerations:

Other Resources

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on penetrating ocular trauma

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on corneal lacerations

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on iris prolapse

Proceedings articles that discuss acute ocular trauma

Small Animal Radiology & Ultrasonography: Ultrasonography of the Eye/Globe

Eye Injuries First Aid

Ophthalmology Fun Case 18

For more images see these slideshows in the Image Library:

Corneal Perforation & Penetrations, Part 1 – Cat

Corneal Perforation & Penetrations, Part 2 – Cat

Ocular Trauma – Cat

Scleral Lesions – Cat

Differential Diagnosis:

Most penetrating injuries are obvious upon thorough examination. A major differential consideration is corneal rupture associated with a deep or melting corneal ulcer. Ruptured corneal ulcers may produce signs similar to a traumatic corneal perforation; however, clinical examination usually allows discrimination of the two conditions.

References:

- Rampazzo A, Eule C, Speier S, et al: Scleral rupture in dogs, cats, and horses. Vet Ophthalmol 2006 Vol 9 (3) pp. 149-55.

- Spiess BM, Rühli MB, Bolliger J: [Eye injuries in the dog caused by cat claws]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 1996 Vol 138 (9) pp. 429-33.

- Paulsen ME, Kass PH: Traumatic corneal laceration with associated lens capsule disruption: a retrospective study of 77 clinical cases from 1999 to 2009. Vet Ophthalmol 2012 Vol 15 (6) pp. 355-68.

- Guerreiro CE, Appelboam H, Lowe RC: Successful medical treatment for globe penetration following tooth extraction in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2014 Vol 17 (2) pp. 146-49.

- Smith MM, Smith EM, La Croix N, et al: Orbital penetration associated with tooth extraction. J Vet Dent 2003 Vol 20 (1) pp. 8-17.

- Davidson MG, Nasisse MP, Jamieson VE, et al: Traumatic anterior lens capsule disruption. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1991 Vol 27 (4) pp. 410-14.

- Miller PE: Uvea. In: Maggs DJ, Miller PE, Ofri R (eds): Slatter’s Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology, 4 ed. Elsevier, St. Louis MO 2008 pp. 203-29.

- Ledbetter EC, Gilger BC: Diseases of the Canine Cornea and Sclera. In: Gelatt KN (ed): Veterinary Ophthalmology, 5 ed. Wiley-Blackwell, Ames IA 2013 pp. 976.

- Lacerda RP, Gimenez MT, Laguna F, et al: Corneal grafting for the treatment of full-thickness corneal defects in dogs: a review of 50 cases. Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (3) pp. 222-31.

- Costa D, Leiva M, Sanz F, et al: A multicenter retrospective study on cryopreserved amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment of complicated corneal ulcers in the dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2019 Vol 22 (5) pp. 695-702.

- Wood C, Scott EM: Feline ocular post-traumatic sarcomas: Current understanding, treatment and monitoring. J Feline Med Surg 2019 Vol 21 (9) pp. 835-42.

- Fenollosa-Romero E, Jeanes E, Freitas I, et al: Outcome of phacoemulsification in 71 cats: A multicenter retrospective study (2006-2017). Vet Ophthalmol 2020 Vol 23 (2) pp. 141-47.

- Plunkett SJ: Anaphylaxis to ophthalmic medication in a cat. J Vet Emerg Crit Care (San Antonio) 2000 Vol 10 (3) pp. 169-71.

- Hume-Smith KM, Groth AD, Rishniw M, et al: Anaphylactic events observed within 4 h of ocular application of an antibiotic-containing ophthalmic preparation: 61 cats (1993-2010). J Feline Med Surg 2011 Vol 13 (10) pp. 744-51.

- Perry R, Moore D, Scurrell E: Globe penetration in a cat following maxillary nerve block for dental surgery. J Feline Med Surg 2015 Vol 17 (1) pp. 66-72.

- Volk HA, Bayley KD, Fiani N, et al: Ophthalmic complications following ocular penetration during routine dentistry in 13 cats. N Z Vet J 2019 Vol 67 (1) pp. 46-51.

- Dalesandro N, Stiles J, Miller M: Septic lens implantation syndrome in a cat. Vet Ophthalmol 2011 Vol 1 (0) pp. 84-87.

- Sandmeyer LS, Bowen G, Grahn BH: Diagnostic ophthalmology. Anterior uveitis, cataract, retinal detachment, and an intraocular foreign body. Can Vet J 2007 Vol 48 (9) pp. 975-76.

- Glaze MB, Maggs DJ, Plummer CE: Feline Ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, Benpshlomo G, Gilber BC, et al (eds): Veterinary Ophthalmology, 6 ed. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken NJ 2021 pp. 1665-840.

- Volk HA, Bayley KD, Fiani N, et al: Ophthalmic complications following ocular penetration during routine dentistry in 13 cats. N Z Vet J 2019 Vol 67 (1) pp. 46-51.

- Braus BK, Tichy A, Featherstone HJ, et al: Outcome of phacoemulsification following corneal and lens laceration in cats and dogs (2000-2010). Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (1) pp. 4-10.

Feedback:

If you note any error or omission or if you know of any new information, please send your feedback to VINcyclopedia@vin.com.

If you have any questions about a specific case or about this disease, please post your inquiry to the appropriate message boards on VIN.