Corneal Erosion, Persistent in Dogs

Published by Emily A. Latham, DVM

Last updated on 5/31/2024.

Contributors:

Revised by Emily A. Latham MVB and Rachel L. Davis DVM, MS, DACVO

Revised by Pilar Camacho-Luna LV, 10/16/2019

Original author was Terah Webb DVM, DACVO, 9/21/2012

Synonyms:

Boxer corneal ulcer

Indolent corneal ulcer

Nonhealing corneal ulcer

Refractory cornel ulcer

Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defect

Disease Description:

Definition

Persistent corneal erosions are uninfected, epithelial defects with a nonadherent epithelial border. Corneal stroma is intact. Also known as spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defect (SCCED), the lesion is characterized by failure to heal within 2 weeks via normal wound healing processes. Persistent erosions are the most common type of refractory corneal ulcers in the dog. They can be present for weeks to months.

Anatomy

Cornea is comprised of 4 layers, namely epithelium, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. Epithelium contains 5-7 layers of nonkeratinized squamous, polyhedral (wing), and basal cells. Beneath the epithelium lies a basement membrane. Hemidesmosomes attach the basement membrane of the basal cells to the underlying stroma.

Superficial corneal ulcers occur with loss of the epithelial layer. Epithelial cells have great regenerative power, with a basal cellular turnover time of 7 days. Under normal circumstances, if the entire corneal epithelium is removed the cornea will resurface in most species within 48-72 hours.1 However, the basement membrane can take weeks to months to reestablish, and corneal epithelium can be easily removed until the basement membrane is reformed.37

Pathophysiology

Pathophysiology of SCCEDs is not fully elucidated; however, several morphologic and functional abnormalities are described in dogs. In one study, the majority of cases had poorly-attached epithelium, dysmaturation, and loss of basement membrane.2 The most common histological feature was a distinctive, superficial stromal band characterized by a thin, hyalinized acellular zone that created a physical barrier between the epithelium and adhesion complexes.2 These changes resulted in lack of adhesion of newly formed epithelium to the adjacent stroma, leaving it susceptible to shearing forces of the eyelids.

Etiology

Most SCCEDs in dogs are considered spontaneous because no historical inciting event is ever identified. A defect in the NOG gene increases the risk of SCCED in the boxer breed.34 It is possible that mild trauma or other corneal diseases may contribute. Concurrent ocular (e.g. keratoconjunctivitis sicca, eyelid tumors, endothelial degeneration) and systemic diseases may predispose older dogs to SCCEDs. Bilateral erosions have been associated with corticosteroid therapy and hyperadrenocorticism.3

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings/History: History of a chronic (>2 weeks), nonhealing corneal ulcer is a characteristic feature.2,38 Pain is variable. Varying degrees of epiphora, blepharospasm, and conjunctival hyperemia may be present.

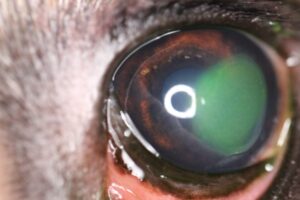

Ocular Examination Findings: The ulcer can occur in any quadrant of the cornea and is very superficial. A ring of loose epithelium surrounds the erosion and creates a halo of less intense fluorescein staining from diffusion of fluorescein beneath the loose epithelium (Figure 1A). If loose epithelium is not obvious and the ulcer is superficial, a topical anesthetic agent (e.g. proparacaine) can be applied and the ulcer site gently rubbed with a sterile cotton swab. If epithelium moves with the swab, diagnosis is confirmed.

Corneal neovascularization (Figure 2A) occurs in 58-64% of affected eyes.2,10 Degree of vascularization partially depends on size and duration (chronicity) of the ulcer. In chronic cases, variable amounts of granulation tissue can also develop within the ulcer bed (Figure 3A). The boxer is more likely to form excessive vascularization and granulation than some other breeds. Focal stromal edema may be present under the ulcer (Figure 1A). The presence of diffuse corneal edema is suggestive of endothelial disease and may represent a contributing cause of the erosion. SCCEDs do not cause diffuse corneal edema. Most persistent erosions are unilateral but bilateral ulcers can occur. SCCEDs may also occur in the contralateral eye at some other time in the dog’s life. Most eyes have only one erosion; however, multiple sites can be affected (Figure 4A).

Secondary uveitis, stromal infection (e.g. yellow, white discoloration), and stromal malacia are not components of SCCEDs. Other primary causes of corneal ulcers and delayed wound healing are also absent.

Cytology: Cytology is not required to make a diagnosis. However, if corneal cytology is performed it often shows mild, neutrophilic inflammation.2 Infectious organisms are absent.

Culture: Culturing of the cornea is not usually necessary and does not yield growth of microorganisms.

Disease Description in This Species:

Signalment

Although SCCEDs can occur in any breed and mixed-breed dogs, the boxer, golden retriever, Pembroke Welsh corgi, West Highland white terrier, and possibly the Labrador retriever and Staffordshire bull terrier are predisposed.3-7 SCCEDs occur most often in middle-aged to older dogs (mean 8 years, rang 3-14 years).3,5,8,9 No sex predisposition has been reported.

Clinical Signs

Potential signs include tearing, tear staining near the medial canthus, blepharospasm, pawing or rubbing at the eye, conjunctival redness, and visible cloudiness in the cornea.

Etiology:

Corticosteroid administration

Genetic, hereditary

Hyperadrenocorticism

Idiopathic, unknown

Trauma

Breed / Species Predilection:

Boxer

Golden retriever

Labrador retriever

Pembroke Welsh corgi

Staffordshire terrier, American/bull

West Highland white terrier

Sex Predilection:

None

Age Predilection:

Mature, middle-aged

Clinical Findings:

AFEBRILE

Blepharospasm, eye pain

Conjunctival congestion, hyperemia

CONJUNCTIVITIS

Corneal opacity

Corneal scarring

Corneal ulcer, keratitis

Corneal vascularization

Edema corneal

EDEMA or SWELLING

Epiphora, lacrimation increased

Eyelid pruritus, rubbing

Keratoconjunctivitis

OCULAR DISCHARGE

Ocular discharge serous

PAIN

Third eyelid, nictitating membrane prolapsed

ULCERS

ZZZ INDEX ZZZ

| Diagnostic Procedures: | Diagnostic Results: | |

| Cytology, biopsy of conjunctiva or cornea | Neutrophilic inflammation of conjunctiva | |

| Ocular examination | Corneal fluorescein staining positive | |

| Loose epithelium over corneal erosion |

Images:

6-yr-old boxer. Note fluorescein stain under the loose edges of the ulcer.

6-yr-old boxer. Photo taken 18 days after diamond burr procedure. Note mild fibrosis (haze) at the site.

9-yr-old Labrador retriever. Loose epithelium overlays the neovascularization.

9-yr-old Labrador retriever. Photo taken 17 days after diamond burr procedure. Vascularization has resolved and the eye is comfortable.

10-yr-old golden retriever. Note raised granulation tissue within the ulcer bed.

10-yr-old golden retriever. Photo taken 15 days after diamond burr procedure. Granulation tissue has resolved and only mild fibrosis is visible at this time. Corneal is smooth and eye is comfortable.

Treatment / Management:

SPECIFIC THERAPY

Specific therapy involves removal of all loose epithelium and the acellular hyaline zone, with additional promotion of adherence of new epithelium as it migrates across the ulcer bed.

Debridement

Under topical anesthesia (e.g. proparacaine) debridement is performed using a dry, sterile cotton swab. As the swab is rubbed from the center of the ulcer towards the edge, it catches, lifts, and strips off loose epithelium. Normal, adherent epithelium cannot be removed with a cotton swab, so debridement should extend peripherally until no further epithelium can be removed. Success with debridement alone varies between studies, with an average of about 50%.1,3,8,11 Adequate time must be given for new epithelium to migrate across the defect and adhere to the underlying stroma, so debridement should not be performed more frequently than every 10-14 days.

Debridement and Grid/Punctate Keratotomy

Under topical anesthesia, loose epithelium is debrided as described above. Keratotomy can also be performed under sedation or general anesthesia, if the patient requires it.3,8,9 After debridement, superficial punctures or striae (Figure 4B) are made using a 22 or 25-gauge needle in the anterior stroma over the entire debrided surface. Specific, set-depth needles are also available for anterior stromal puncture. Debridement with keratotomy has a higher success than debridement alone (average healing rate 80%).1 Debridement and keratotomy may be repeated every 14 days as necessary.

Debridement and Diamond Burr Keratotomy

Under topical anesthesia, sedation, or general anesthesia, debridement of all loose epithelium is performed as described above and followed by diamond burr keratotomy (DBK).12-15,35 The size and the shape of the diamond burr tip does not appear to affect outcome.16 Debridement and DBK has a greater success rate than grid or punctate keratotomy.12,14,17,18 First time success rates can be >85%.1 Complications are rare but include bullous keratopathy and keratomalacia.15,17,18 It is theorized that these complications may be related to accumulation of organic contaminants on the tip of the diamond burr instrument.14 It is essential to appropriately clean and sterilize the tips prior to each use. Debridement and DBK has become more common than grid or punctate keratotomies in recent years.14,15

Superficial Keratectomy

Superficial keratectomy achieves healing by removal of the superficial stromal acellular hyalinized zone and exposing underlying corneal collagen.4,8 It is also effective in treating nonhealing ulcers secondary to endothelial disease and subsequent corneal edema.19 Surgical keratectomy is usually reserved for recurrent erosions that do not heal with debridement and keratotomies. It requires general anesthesia; magnification (e.g. operating microscope); good knowledge of corneal anatomy; and microsurgical skills and instrumentation. For these reasons, referral to an ophthalmologist is typically necessary. Success rate consistently approaches 100%.4,8

Thermal Keratoplasty (TKP)

Following debridement of loose epithelium, punctate keratotomy is performed using a fine, low-temp, ophthalmic cautery.20 Heat at the cautery tip breeches abnormal basement membrane in the ulcer bed and disperses stromal edema. TKP is usually performed under sedation or general anesthesia. It is done most often in eyes with pre-existing stromal edema or for ulcers that are refractory to other therapies. Excessive cauterization can result in significant scarring, with potential impairment of vision if the ulcer is located in the pupillary axis.

SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

Any concurrent ocular disease that may have predisposed the affected dog to a recurrent erosion must also be addressed. See the Canine VINcyclopedia chapters on Keratoconjunctivitis sicca and Corneal edema for further therapeutic advice. An Elizabethan collar is often applied to prevent self-trauma that can worsen the ulcer. Keep in mind that corneal pain is often transiently worse after debridement and the above procedures. Topical antibiotics are administered q 8-12 hrs to prevent secondary infection. Topical oxytetracycline and/or oral doxycycline have been shown to promote mesenchymal transformation of epithelial cells and encourage faster healing.22 However, in one study of affected canine eyes, healing time was significantly faster when ofloxacin was administered in comparison to oxytetracycline and tobramycin.18

Analgesics are indicated because SCCEDs can cause pain from exposure of corneal nerves and from reflex ciliary spasm. Atropine 1% or morphine 1% may be administered topically. Prolonged use of atropine can decrease tear production. Systemic analgesics (gabapentin 5-10 mg/kg PO q 12-24 hrs; tramadol 2-4 mg/kg PO q 12 hrs) and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be considered. Topical proparacaine is not indicated for chronic pain control and should not be used on a repeated basis. The drug is toxic to corneal epithelium and exhibits tachyphylaxis, i.e. it becomes less effective with recurrent application.

Bandage contact lens may decrease time to healing. Contact lenses also alleviate pain associated with the eyelids rubbing against the corneal erosion.3,18,24,25

Various topical medications have been tried that are designed to promote healing by improving the bond between epithelium and stroma; by decreasing mechanical disruption of epithelial movement/adhesion from eyelid movement (i.e. blinking); or by lubricating the cornea. They include ophthalmic chondroitin sulfate solution (not available in the USA), hyaluronic acid gel, polysulfated glycosaminoglycans, and topical epidermal growth factor.26-30 Good success with DBK has largely made these supportive measures unnecessary. Although advocated by some clinicians, use of autogenous serum or platelet-rich plasma does not improve healing rates.31-32,36

MONITORING and PROGNOSIS

Ulcers are typically rechecked every 10-14 days; however, visits may be scheduled more frequently if clinical signs worsen. Persistent erosions can be very frustrating to treat and often require prolonged therapy. While many ulcers heal within a month following debridement and interventive therapy, some ulcers require months of therapy and the use of different types of procedures before they heal.3,4,8,9,12,26,29,33 Once the ulcer is healed, superficial vascularization, granulation tissue, and focal corneal edema usually subside within 2-3 weeks (Figures 2B, 3B). Mild fibrosis may persist for longer (Figure 1B).

Special Considerations:

Other Resources

Recent Message Board discussions on persistent corneal erosions

Proceedings articles that discuss refractory, nonhealing corneal ulcers

Client handout on corneal ulcers and erosions in dogs and cats

2014 VIN Rounds on nonhealing corneal ulcers/erosions

Challenging and Fun Cases:

Ophthalmology Fun Case 118

Ophthalmology Fun Case 136

Ophthalmology Fun Case 141

VIN Mentor Procedures video on corneal debridement, diamond burr keratotomy, grid keratotomy, and contact lens placement

For more images see the Persistent Corneal Erosions, Part 1 – Dog and Persistent Corneal Erosions, Part 2 – Dog slideshows in the Image Library

Differential Diagnosis:

Corneal sequestrum

Other causes of corneal vascularization

Other types of ulcerative keratitis

References:

-

- Ledbetter EC, Gilger BC: Diseases and Surgery of the Canine Cornea and Sclera. Veterinary Ophthalmology, 5th ed. Blackwell, Ames IA 2013 pp. 976-1049.

- Bentley E, Abrams GA, Covitz D, et al: Morphology and immunohistochemistry of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCED) in dogs. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001 Vol 42 (10) pp. 2262-69.

- Morgan R, Abrams K: A comparison of six different therapies for persistent corneal erosions in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1994 Vol 4 (1) pp. 38-43.

- Peiffer RL, Gelatt K, Gwin RM: Superficial keratectomy in the management of indolent ulcers in the boxer cornea. Canine Pract 1976 Vol 3 pp. 31-33.

- Kirschner SE, Niyo Y, Betts DM: Idiopathic persistent corneal erosions : Clinical and pathological findings in 18 dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1989 Vol 25 (1) pp. 84-90.

- Scherrer K: [Histological studies of the pathology of recurrent corneal erosion in the German Boxer dog]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 1983 Vol 125 (6) pp. 337-44.

- Jeanes EC: Management of superficial chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) in dogs with multiple punctate keratotomy with a third-eyelid flap. Proceed Brit Assoc Vet Ophthalmol 2016 Vol 11 (1) pp. 25-26.

- Stanley R, Hardman C, Johnson B: Results of grid keratotomy, superficial keratectomy and debridement for the management of persistent corneal erosions in 92 dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 1998 Vol 1 (4) pp. 233-38.

- Champagne E, Munger R: Multiple punctate keratotomy for the treatment of recurrent epithelial erosions in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1992 Vol 28 (3) pp. 213-16.

- Murphy CJ, Marfurt CF, McDermott A, et al: Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCED) in dogs: Clinical features, innervation, and effect of topical SP, with or without IGF-1. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2001 Vol 42 (10) pp. 2252-61.

- Willeford K, Miller W, Abrams K: Modulation of proteolytic activity associated with persistent corneal ulcers of dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 1998 Vol 1 (1) pp. 5-8.

- Gosling AA, Labelle AL, Breaux CB: Management of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) in dogs with diamond burr debridement and placement of a bandage contact lens. Vet Ophthalmol Online 2013 Vol 16 (2) pp. 83-88.

- Dawson C, Naranjo C, Sanchez-Maldonado B, et al: Immediate effects of diamond burr debridement in patients with spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects, light and electron microscopic evaluation. Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (1) pp. 11-15.

- Spertus CB, Brown JM, Giuliano EA: Diamond burr debridement vs. grid keratotomy in canine SCCED with scanning electron microscopy diamond burr tip analysis. Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (6) pp. 505-13.

- Wu D, Smith SM, Stine JM, et al: Treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) with diamond burr debridement vs combination diamond burr debridement and superficial grid keratotomy. Vet Ophthalmol 2018 Vol 21 (6) pp. 622-31.

- Visser HE, Teixeira LB, Budelsky CL: Histological evaluation of corneal wounds experimentally created using diamond burr debridement in canine eyes: comparison of debridement and variation of butt tips [abstract]. Vet Ophthalmol 2015 Vol 18 (6) pp. E33.

- Sila GH, Morreale RJ, Lorimer DW, et al: A retrospective evaluation of the diamond burr superficial keratectomy in the treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs from 2006 to 2008 [abstract]. Proceed Am Coll Vet Ophthalmol 2009 Vol 12 (6) pp. 390-409.

- Dees DD, Fritz KJ, Wagner L, et al: Effect of bandage contact lens wear and postoperative medical therapies on corneal healing rate after diamond burr debridement in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (5) pp. 382-89.

- Bayley KD, Read RA, Gates MC: Superficial keratectomy as a treatment for non-healing corneal ulceration associated with primary corneal endothelial degeneration. Vet Ophthalmol 2019 Vol 22 (4) pp. 485-92.

- Bentley E, Murphy CJ: Thermal cautery of the cornea for treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs and horses. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2004 Vol 224 (2) pp. 250-3, 224.

- Chandler HL, Gemensky-Metzler AJ, Bras ID, et al: In vivo effects of adjunctive tetracycline treatment on refractory corneal ulcers in dogs. JAVMA 2010 Vol 237 (4) pp. 378-86.

- Spatola RA, Thangavelu M, Chandler HL: The effects of topical nalbuphine on canine corneal cells in vitro. Proceed Am Coll Vet Ophthalmol Proceed Am Coll Vet Ophthalmol 2009.

- Clark JS, Bentley E, Smith LJ: Evaluation of topical nalbuphine or oral tramadol as analgesics for corneal pain in dogs: a pilot study. Vet Ophthalmol 2011 Vol 14 (6) pp. 358-64.

- Grinninger P, Verbruggen AM, Kraijer-Huver IM, et al: Use of bandage contact lenses for treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs. J Small Anim Pract 2015 Vol 56 (7) pp. 446-49.

- Wooff PJ, Norman JC: Effect of corneal contact lens wear on healing time and comfort post LGK for treatment of SCCEDs in boxers. Vet Ophthalmol 2015 Vol 18 (5) pp. 364-70.

- Ledbetter RJ, Munger RJ, Ring RD, et al: Efficacy of two chondroitin sulfate ophthalmic solutions in the therapy of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects and ulcerative keratitis associated with bullous keratopathy in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2006 Vol 9 (2) pp. 77-87.

- Yang G, Espandar L, Mamalis N, et al: A cross-linked hyaluronan gel accelerates healing of corneal epithelial abrasion and alkali burn injuries in rabbits. Vet Ophthalmol 2010 Vol 13 (3) pp. 144-50.

- Williams DL, Wirostko BM, Gum G, et al: Topical Cross-Linked HA-Based Hydrogel Accelerates Closure of Corneal Epithelial Defects and Repair of Stromal Ulceration in Companion Animals. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2017 Vol 58 (11) pp. 4616-22.

- Miller WW: Using polysulfated glycosaminoglycan to treat persistent corneal erosions in dogs. Vet Med 1996 Vol 91 (12) pp. 916-22.

- Kirschner SE, Brazzell RK, Stern ME, et al: The use of topical epidermal growth factor for treatment of nonhealing corneal erosions in dogs. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1991 Vol 27 (4) pp. 449-452.

- Eaton JS, Hollingsworth SR, Holmberg BJ, et al: Effects of topically applied heterologous serum on reepithelialization rate of superficial chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2017 Vol 250 (9) pp. 1014-22.

- Edelmann ML, Mohammed HO, Wakshlag JJ, et al: Clinical trial of adjunctive autologous platelet-rich plasma treatment following diamond-burr debridement for spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2018 Vol 253 (8) pp. 1012-21.

- Bentley E: Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2005 Vol 41 (3) pp. 158-64.

- Meurs KM, Montgomery K, Friedenberg SG, et al: A defect in the NOG gene increases susceptibility to spontaneous superficial chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCED) in boxer dogs. BMC Vet Res 2021 Vol 17 (1) pp. 254.

- Hung JH, Leidreiter K, White JS, et al: Clinical characteristics and treatment of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects (SCCEDs) with diamond burr debridement. Vet Ophthalmol 2020 Vol 23 (4) pp. 764-69.

- Dees DD, Keys DA: Use of autologous serum or Vizoovet to improve healing rates of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects after diamond burr debridement in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2022 Vol 25 (1) pp. 6-11.

- Glaze MB, Maggs DJ, Plummer CE: Feline ophthalmology. In: Gelatt KN, Ben-Schlomo G, Gilberg BC, et al (eds): Veterinary Ophthalmology Wiley-Blackwell, Hoboken NJ 2021 pp. 1645-1880.

- Da Silva EG, Powell CC, Gionfriddo JR, et al: Histologic evaluation of the immediate effects of diamond burr debridement in experimental superficial corneal wounds in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2011 Vol 14 (5) pp. 285-91.

Feedback:

If you note any error or omission or if you know of any new information, please send your feedback to VINcyclopedia@vin.com.

If you have any questions about a specific case or about this disease, please post your inquiry to the appropriate message boards on VIN.