Published by Emily A. Latham, DVM

Last updated on 7/15/2024.

Contributors:

Revised by Emily A. Latham MVB and Rachel L. Davis DVM, MS, DACVO

Revised by Pilar Camacho-Luna LV, 11/1/2019

Original author was Ralph E. Hamor DVM, MS, DACVO, 3/15/2012

Synonyms:

Traumatic corneal perforation

Traumatic globe rupture

Traumatic scleral perforation

Disease Description:

Definition

Penetrating ocular trauma refers to any full-thickness injury of the globe from a traumatic event. Sometimes the injury occurs through the cornea and is visible to the observer. Sometimes trauma occurs through the sclera, and direct observation of the injury is obscured by conjunctiva, eyelids, and other orbital tissues. The bony orbit of dogs and cats provides excellent protection of the globe from blunt trauma. The globe is more commonly affected by penetrating trauma. When blunt trauma causes scleral disruption/rupture, the injury is treated like penetrating trauma.1

Etiology

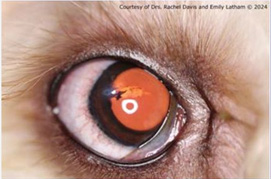

The most common cause of penetrating trauma in puppies is from a cat scratch (Figure 1A).2,3 The injury is most likely to occur when a new puppy is introduced into the home and meets the cat for the first time. Penetrating bite wounds are more common in dogs, especially in little-dog versus big-dog altercations, intact male dogs, and dogs used for fighting. Hunting dogs are commonly exposed to plant foreign bodies, and sticks, awns, and thorns are the most common substances to penetrate the eye. Porcupine quills are the second most common ocular foreign body.14

Various projectiles can penetrate the globe. Hunting dogs or dogs that roam free are most likely to be exposed to lead or steel buckshot. This type of gunshot wound can affect the whole head and other parts of the body. Guard dogs or dogs exposed to criminal or abusive activities may be subjected to bullet wounds.4 Guard, law-enforcement, search-and-rescue, and military dogs may be exposed to industrial and building refuse, explosives, and natural debris.

Migrating foreign bodies that enter the mouth or head may also eventually penetrate the eye. Examples include porcupine quills, sticks, plant awns, sewing needles, etc. Aspiration of the orbit or infiltration of injectable anesthetics into the retrobulbar space can potentially result in iatrogenic penetration of the globe, especially with poor technique. Dental cleaning procedures, especially those involving tooth extractions from the maxillary arcade, can also result in accidental penetration of the globe.5,6 Although uncommon, globe penetration associated with dental procedures is reported more often in cats than dogs.

Pathophysiology

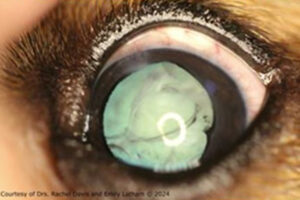

Following trauma, alterations within the eye vary depending upon the location and type of injury. All injuries result in secondary uveitis. Aqueous flare, miosis, dyscoria, and swelling/inflammation of the iris may occur. Hyphema and posterior segment hemorrhage can occur. Although minor lacerations of the lens capsule can heal with fibrosis (Figure 2A), disruption of the lens can result in cataract formation (Figure 2B) and phacoclastic uveitis.

Injuries to the cornea may be associated with fibrin deposition at the site of penetration, iris prolapse, and stromal edema. Severe lacerations or penetrating injuries to the cornea and sclera may cause loss of aqueous humor and collapse of the globe. Severe, extensive, or posterior segment injuries may lead to blindness. Retinal detachment is also possible. Involvement of the orbit may result in orbital cellulitis.

Secondary infection (e.g. endophthalmitis, panophthalmitis, septic implantation of lens) may develop with exposure to natural materials that decompose over time, such as wood, vegetation, porcupine quills, etc.13,14 In addition to these items, materials that oxidize (e.g. iron, steel) cause severe intraocular inflammation. Inert projectiles (e.g. gold, silver, stone, carbon, glass, rubber) are less irritating than mercury, lead, aluminum, zinc, and nickel. Materials composed of copper, bronze, and brass may result in localized abscessation.

Diagnosis

Physical Examination Findings/History: Generally, the owner is aware that some sort of acute trauma has occurred. However, it is important to ask questions regarding the animal’s environment, temperament, presence of other pets in the household, the pet’s job, whether it is confined, and its most recent activities. New introduction to other animals, especially cats, may be reported. If head and/or systemic trauma is obvious, perform oral and physical examinations to determine the extent of injuries elsewhere. Depending on the origin of the wound, periocular hemorrhage and bruising, wounds to the eyelids, head, and face, as well as facial fractures may be detected. More serious systemic injuries (e.g. thoracic, abdominal, subcutaneous) can occur with trauma from projectiles.

Ophthalmic Examination Findings: Examination of the eye is facilitated by application of topical proparacaine. In some animals, sedation or general anesthesia may also be required. Careful manipulation of the eyelids is important to avoid further damage to the globe. All ocular surfaces are examined with magnification. Schirmer tear test and intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement are not done in acute cases with an obvious defect of the cornea because of the risk of causing further damage. IOP is only measured if the trauma is thought to be chronic (old). Air bubbles within the anterior chamber are indicative of globe perforation.

Be sure to assess cranial nerve reflexes, including palpebral reflex, corneal sensitivity, pupillary light reflexes, dazzle and menace responses. Results help determine prognosis for vision and retention of the globe.

If the equatorial or posterior sclera is penetrated, few overt clinical abnormalities may be noted in the anterior segment. However, subconjunctival hemorrhage is typically present. In these cases, complete examination of the lens, vitreous, and fundus is very important. Dilation of the pupil facilitates a more complete examination. Thorough examination of the opposite eye is also indicated.

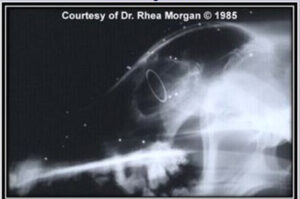

Radiography: Plain radiographs of the skull identify metallic or bony foreign material and accompanying bony fractures. The location of the eye can be marked with a metallic ring (Flieringa fixation ring, Figure 3A) placed on the limbus. This helps identify foreign objects that lie close to or within the globe. Neck, chest, and abdominal x-rays may also be warranted to rule out additional trauma, or the presence of more foreign bodies.

Ultrasonography: An important step following penetrating injury is to determine what ocular structures have been affected. Clinical examination alone may be insufficient for making this determination, especially if opacification of ocular media (e.g. aqueous flare, hyphema, vitreal hemorrhage) prohibits examination of the interior of the globe, or if the rupture is equatorial or posterior. If globe integrity is adequate, ocular ultrasonography may help determine the presence of lens capsule rupture, a foreign body (Figure 3B), vitreal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment.13 Ultrasonography is also useful in cases of suspected scleral rupture. However, following penetrating trauma the pressure applied by the probe on the eye can worsen damage to the globe.

Ultrasonography can be done awake, or under general anesthesia when the patient is intractable, painful, or the globe is unstable. Even with ocular ultrasonography, it may not be possible to visualize small tears in the lens capsule, and inflammatory debris or hemorrhage may mask a retinal detachment. Evaluation by a veterinary ophthalmologist may be considered in such instances.

Advanced Imaging: Computed tomography (CT) may be indicated if penetrating injury has been caused by projectiles that may still be present within the eye (Figure 3C) or have penetrated the skull. Foreign bodies may be easier to identify with CT than plain radiographs depending on the material. CT systems can create 3D reconstructions that are especially useful in evaluation of head trauma and suspected fractures. Magnetic resonance imaging is avoided if penetrating material is potentially composed of ferrous metals.

Other Tests: Bacterial cultures may be positive or negative depending upon the duration and origin of the injury. Cultures are most likely to be positive with endophthalmitis from cat scratch injuries or penetrating material that can necrose (e.g. plant material). High-speed projectiles generate enough heat upon entering tissues that they are unlikely to result in bacterial infections unless the entry wound remains open. Cytology of aqueous humor and other secretions may rarely show bacteria.

Disease Description in This Species:

Signalment

Young puppies are more likely to sustain eye trauma from a cat or other pet scratch because of their playful temperament and lack of menace response. Brachycephalic breeds are also predisposed to ocular trauma due to their large palpebral fissures and exposed eyes. Intact male dogs are more likely to fight with another dog, and that activity may result in an eye injury. Dogs that are used for hunting, guarding, military, and other professional work are predisposed to specific types of injuries that may affect the eye. One study found an increased likelihood of corneal foreign bodies in the winter months, which was thought to correlate with the working season for hunting dogs.14

Clinical Signs

Acute onset of pain is common and manifested by blepharospasm and tearing. If the cornea has been penetrated, generally a gray-white corneal opacity with a plug of fibrinous material and adjacent corneal edema are present. Hemorrhage from the site may also be noted. Foreign material that caused the penetration may or may not be visible. A foreign body may be hidden by corneal edema or ulceration, especially if the wound is not acute. The longer the corneal wound is present, the greater the vascular and/or stromal edematous response, and the more severe the anterior uveitis. Sharp foreign bodies (e.g. thorns) may penetrate deeply as opposed to cupped or nonlinear foreign bodies (e.g. seed husks) that tend to remain more superficial.14

Signs of anterior uveitis include aqueous flare, fibrin or hypopyon in the anterior chamber, miosis, and focal or diffuse iritis. The anterior chamber may be shallow or collapsed. Collapse of the chamber may result in wrinkling of the cornea. Hyphema may be present. Wounds to the cornea may result in iris prolapse, with dyscoria and anterior synechia. If the lens capsule is disrupted, significant signs of anterior uveitis along with protrusion of lens material into the anterior chamber may be noted. However, it can be difficult to determine if anterior lens capsule rupture is present from clinical observation alone, especially if the pupil is miotic. Mydriatics can be administered to improve visibility of the lens.

Signs of penetration into the posterior segment include vitreal inflammation, vitreal hemorrhage, and retinal detachment. Significant lesions within the anterior segment or vitreous that result in cloudiness can preclude accurate visual examination of the fundus.

Etiology:

Bite wound

Cat scratch

Explosions

Foreign body

Gunshot wounds

Hymenoptera sting (bees, wasps, hornets, ants)

Idiopathic, unknown

Penetrating wounds

Plant awns, burrs, splinters

Trauma

Trauma, abuse/malicious/non-accidental

Trauma, motor vehicle/automobile

Breed / Species Predilection:

Brachycephalic breeds

Hunting dogs

Working dogs

Sex Predilection:

Male

Age Predilection:

Juvenile

Young adult

Clinical Findings:

AFEBRILE

Anisocoria, pupils unequal

Anorexia, hyporexia

Bite, puncture wound

Blepharitis

Blepharospasm, eye pain

BLINDNESS OR OTHER VISUAL DEFICIT

Blindness partial, visual deficit

Conjunctival congestion, hyperemia

Conjunctival hemorrhage

CONJUNCTIVITIS

Corneal laceration

Corneal opacity

Corneal scarring

Corneal ulcer, keratitis

Corneal vascularization

Dyscoria

Edema conjunctiva, chemosis

Edema corneal

EDEMA or SWELLING

Edema or swelling cutaneous

Edema or swelling eyelid

Edema or swelling face, head

Edema or swelling orbital, periorbital

Edema or swelling periocular

Endophthalmitis

Enophthalmos

Epiphora, lacrimation increased

Episcleral injection/congestion

Eye small

Facial malformation

HEMORRHAGE

Iris prolapse

Keratoconjunctivitis

Lens luxation, subluxation

MASS

Mass, corneal

Mass, scleral

Menace response absent or decreased

Miosis

MYDRIASIS

OCULAR DISCHARGE

Ocular discharge hemorrhagic

Ocular discharge purulent

Ocular discharge serous

PAIN

PHOTOPHOBIA

Pupillary light reflex absent

Pupillary light reflex decreased

Scleral hemorrhage

Scleral laceration

Synechia, anterior

Third eyelid, nictitating membrane prolapsed

ULCERS

UVEITIS

Uveitis, anterior

| Diagnostic Procedures: | Diagnostic Results: | |

| Radiography of head/skull | Facial fracture | |

| Metallic foreign material visualized | ||

| Ultrasonography of eye/orbit | Disruption or deformity of the lens capsule | |

| Foreign body visualized | ||

| Hyperechoic lens | ||

| Vitreal cavity hemorrhage | ||

| Vitreal debris | ||

| Ocular examination | Aqueous flare | |

| Cataract, lens opacity | ||

| Corneal penetration | ||

| Hyphema, blood anterior chamber eye | ||

| Intraocular pressure normal or decreased on tonometry if uveitis present | ||

| Iridocyclitis, iris/ciliary body inflamed | ||

| Iris-to-cornea or iris-to-lens adhesion | ||

| Retinal detachment | ||

| Retinal hemorrhages | ||

| Scleral penetration | ||

| Third eyelid, nictitating membrane protruded | ||

| Vitreous cloudy | ||

| Computed tomography (CT) or MRI of head | Characterization and extent of the lesion |

Images:

3-yr-old silky terrier with cat scratch. Note dyscoria.

3-yr-old silky terrier. Wound was repaired with a conjunctival graft and corneal transplant.

3-yr-old silky terrier. Cornea has healed with minimal scarring and vascularization.

2-yr-old mini-goldendoodle with lens capsule laceration. Corneal would have sealed. The eye was treated medically.

2-yr-old mini-goldendoodle. Linear cataract and iris pigment from prior posterior synechia are visible but the eye is quiet following medical therapy.

Metal Flieringa fixation ring placed on the limbus denotes location of the globe.

A hyperechoic acoustic shadow is visible immediately posterior to a metallic foreign body.

1-yr-old mixed breed dog. Although the corneal wound has healed, diffuse corneal edema, anterior uveitis and focal hypopyon at the site of lens penetration.

1-yr-old mixed breed dog. Corneal clarity and anterior uveitis are significantly improved.

Treatment / Management:

INITIAL CONSIDERATIONS

Initially, other injuries must be assessed and stabilized. Hemorrhage around the eye should be controlled. After the patient is stabilized, and diagnostic examination and tests are complete, then specific therapy may be instituted. General anesthesia may need to be delayed in the presence of significant head injuries.

SPECIFIC THERAPY

Corneal Wounds

If the rest of the globe is intact (i.e. wound penetrated only the cornea), then a decision must be made as to whether the corneal wound requires repair. Smaller corneal lacerations (i.e. <3 mm) may not require surgery if foreign bodies are not present; the wound is sealed; the anterior chamber is well formed; no leakage of aqueous is occurring; and no iridal/uveal tissue is prolapsed. If unsure how to proceed, then referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended. Superficial corneal foreign bodies may be removed under topical anesthesia if the patient is cooperative.10 Deeper corneal foreign bodies require removal under sedation or general anesthesia and magnification (e.g. operating microscope).10

If the corneal wound is not intact; a large flap was created; the iris is prolapsed (Figure 1A); and/or a foreign body is still present, then surgery to remove the foreign body, and/or repair the cornea is required. The cornea is typically repaired (using an operating microscope) with 8-0 or 9-0 absorbable suture. A conjunctival graft may be placed over the incision after suturing to provide extra support (Figures 1B, 1C). Depending on the location of the wound, conjunctival grafting may reduce vision. Other surgical techniques that may be considered include amniotic membrane and corneal grafts.8,9 These procedures require specialized equipment and expertise and thus referral to a veterinary ophthalmologist is recommended.

Scleral Wounds

Usually repair of a scleral rupture is not possible because of the location of the wound, e.g. equatorial or posterior. Because blindness and phthisis bulbi are common sequela, enucleation is often the only treatment option for extensive scleral lacerations.1 For small tears, medical therapy can be attempted, and may provide adequate cosmesis. However, long-term outcome of medical therapy has not been evaluated and the risk of long-term complications (e.g. chronic pain, panophthalmitis, phthisis bulbi, secondary entropion) must be considered.

Eyelid Wounds

Accompanying eyelid lacerations may also require surgery, especially is they involve the lid margin. See the Canine VINcyclopedia chapter on Adnexal Trauma for more information.

Lens Capsule Wounds

If the lens capsule is lacerated, treatment recommendations vary. One study reported that 45% of eyes with full-thickness corneal trauma had lens involvement, although most cases were minor.10 For many years, lensectomy was advised for capsular tears >1.5 mm, or when substantial herniation of lens cortex material occurred into the anterior chamber.7 Lens proteins are antigens, and exposure of the anterior chamber to large amounts of lens proteins may result in severe granulomatous inflammation (i.e. phacoclastic uveitis) that is unresponsive to medical therapy and can result in blindness. However, small tears may heal via fibrosis (Figure 2B), and a retrospective study demonstrated that even large lens capsule lacerations may respond well to medical therapy alone.3 In this study prognosis was better for eyes that were referred to a veterinary ophthalmologist within 72 hours and were followed carefully for the first 2-4 weeks.3 In one study, excellent outcomes were achieved with phacoemulsification (Figure 4B) and corneal repair for traumatic lacerations involving the cornea and lens.14 Another study reported that >50% of eyes with traumatic corneal laceration with lens capsule rupture lost vision regardless of the therapy.7

Severe Injuries

Aggressive medical therapy can be tried in less severe cases prior to considering enucleation. However, enucleation is indicated in the following instances:

1) Large wounds that affect both cornea and sclera, with herniation or loss of intraocular contents

2) Expulsive injuries, with loss of the lens and/or collapse of the eye

3) Exposed or through-and-through foreign body

4) Injuries accompanied by orbital fractures that displace the globe

5) Corrective surgery delayed because of systemic injuries

6) Attempts at surgical repair and control of uveitis fail

7) Development of infection, chronic endophthalmitis despite appropriate therapy11

8) Lens trauma that predisposes to future intraocular sarcoma

SUPPORTIVE THERAPY

Supportive medical therapy involves both topical and systemic medications.12 Topical bactericidal antibiotic solution (e.g. fluoroquinolone, gentamicin, tobramycin) is administered q 4-8 hrs. Ointments are contraindicated because the oil-based carrier is irritating to intraocular structures. Ophthalmic triple antibiotics are avoided because of the possible risk of anaphylactic reactions in cats.13,14 A topical nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) agent may be administered if hyphema is not present. Topical atropine is given to dilate the pupil and help control pain. Topical anti-fungal agents are often indicated in some cases of vegetative foreign bodies.

Broad-spectrum systemic antibiotics are indicated in many cases. Systemic NSAIDs may be considered once active hemorrhaging is controlled. Systemic pain medication is typically indicated. An Elizabethan collar is applied until the wound heals. Sedation may be needed to keep an anxious or overactive animal quiet for a few days.

Once the corneal wound has healed, topical steroids (e.g. dexamethasone, prednisolone acetate) may be substituted for the topical NSAIDs, especially if severe, secondary uveitis and/or corneal inflammation is present. If intraocular inflammation is considered to be sterile and uncontaminated, oral steroids may also replace oral NSAIDs after an appropriate wash-out period.

MONITORING

Frequent monitoring is crucial for achieving a long-term, successful outcome. Medical therapy is often required for several weeks to months. Development of delayed complications is common, so recheck examinations are often continued for months. Treatment modifications are made depending upon the findings at each examination. Septic lens implantation syndrome can occur following traumatic injuries to the lens and lead to chronic uveitis.11 Development of intraocular sarcoma following lens capsule rupture has been reported in one dog and it was unrelated to trauma.15

PROGNOSIS

Prognosis depends on severity of the injury; presence of complicating systemic injuries; time between injury and institution of therapy; appropriateness of therapy; and type and final location of foreign material involved in the penetration. Potential complications include uveitis, hyphema, cornea scarring, cataract formation, permanent anterior synechiae and dyscoria, secondary glaucoma, endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, vitreal opacities, visual deficits or blindness, and phthisis bulbi. Lack of dazzle reflex and loss of consensual pupillary light response at the initial examination are poor prognostic indicators for vision.

In many cases, prompt attention and treatment can save vision. Penetration of the lens capsule complicates and worsens the prognosis.3,7 Risk factors for increased likelihood of enucleation include full-thickness corneal injuries, intraocular foreign body penetration, severe lens trauma, and/or severe secondary uveitis.10 Penetration of the posterior aspect of the globe is also associated with a worse prognosis. If the orbit has suffered significant damage, it is more likely the globe cannot be salvaged.

Preventive Measures:

Take precautions when introducing a new cat to the household. Make the introduction a gradual one, under close supervision. Until the pets are well accustomed to each other, consider separating them when they are left home alone. Do not allow dogs to roam free. Keep premises free of dangerous materials when guard or law-enforcement dogs are present. Keep small dogs closely restrained when approached by large, unfamiliar dogs. Clearly identify hunting dogs with blaze-orange, fluorescent collars and vests.

Special Considerations:

Other Resources

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on penetrating ocular injuries

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on corneal lacerations

Recent VIN Message Board discussions on iris prolapse

Proceedings articles that discuss acute ocular trauma

Small Animal Radiology & Ultrasonography: Ultrasonography of the Eye/Globe

Eye Injuries First Aid

Ophthalmology Fun Case 111

Ophthalmology Fun Case 143

For more images see these slideshows in the Image Library:

Corneal Perforation & Penetrations, Part 1 – Dog

Corneal Perforation & Penetrations, Part 2 – Dog

Iris Prolapse – Dog

Corneal Ulcers & Wounds – Dog

Ocular/Periocular Trauma – Dog

Ocular Pathology – Dog

Differential Diagnosis:

Most penetrating injuries are obvious upon thorough examination. A major differential consideration is corneal rupture associated with a deep or melting corneal ulcer. Ruptured corneal ulcers may produce signs similar to a traumatic corneal perforation; however, clinical examination usually allows discrimination of the two conditions.

References:

| 1) | Rampazzo A, Eule C, Speier S, et al: Scleral rupture in dogs, cats, and horses. Vet Ophthalmol 2006 Vol 9 (3) pp. 149-55. |

| 2) | Spiess BM, Rühli MB, Bolliger J: [Eye injuries in the dog caused by cat claws]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 1996 Vol 138 (9) pp. 429-33. |

| 3) | Paulsen ME, Kass PH: Traumatic corneal laceration with associated lens capsule disruption: A retrospective study of 77 clinical cases from 1999 to 2009. Vet Ophthalmol 2012 Vol 15 (6) pp. 355-68. |

| 4) | Sansom J, Labruyère J: Penetrating ocular gunshot injury in a Labrador Retriever. Vet Ophthalmol 2012 Vol 15 (2) pp. 115-22. |

| 5) | Guerreiro CE, Appelboam H, Lowe RC: Successful medical treatment for globe penetration following tooth extraction in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2014 Vol 17 (2) pp. 146-49. |

| 6) | Smith MM, Smith EM, La Croix N, et al: Orbital penetration associated with tooth extraction. J Vet Dent 2003 Vol 20 (1) pp. 8-17. |

| 7) | Davidson MG, Nasisse MP, Jamieson VE, et al: Traumatic anterior lens capsule disruption. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 1991 Vol 27 (4) pp. 410-14. |

| 8) | Lacerda RP, Gimenez MT, Laguna F, et al: Corneal grafting for the treatment of full-thickness corneal defects in dogs: a review of 50 cases. Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (3) pp. 222-31. |

| 9) | Costa D, Leiva M, Sanz F, et al: A multicenter retrospective study on cryopreserved amniotic membrane transplantation for the treatment of complicated corneal ulcers in the dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2019 Vol 22 (5) pp. 695-702. |

| 10) | Pont RT, Riera MM, Newton R, et al: Corneal and anterior segment foreign body trauma in dogs: a review of 218 cases. Vet Ophthalmol 2016 Vol 19 (5) pp. 386-97. |

| 11) | Bell CM, Pot SA, Dubielzig RR: Septic implantation syndrome in dogs and cats: a distinct pattern of endophthalmitis with lenticular abscess. Vet Ophthalmol 2013 Vol 16 (3) pp. 180-85. |

| 12) | Lew M, Lew S, Drazek M, et al: Penetrating eye injury in a dog: a case report. Vet Med (Praha) 2015 Vol 60 (4) pp. 213-21. |

| 13) | Sandmeyer LS, Bowen G, Grahn BH: Diagnostic ophthalmology. Anterior uveitis, cataract, retinal detachment, and an intraocular foreign body. Can Vet J 2007 Vol 48 (9) pp. 975-76. |

| 14) | Braus BK, Tichy A, Featherstone HJ, et al: Outcome of phacoemulsification following corneal and lens laceration in cats and dogs (2000-2010). Vet Ophthalmol 2017 Vol 20 (1) pp. 4-10. |

| 15) | Graham KL, Krockenberger MB, Billson FM: Intraocular sarcoma associated with lens capsule rupture and persistent hyperplastic primary vitreous in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2018 Vol 21 (2) pp. 188-93. |

Feedback:

If you note any error or omission or if you know of any new information, please send your feedback to VINcyclopedia@vin.com.

If you have any questions about a specific case or about this disease, please post your inquiry to the appropriate message boards on VIN. Bottom of Form